G Squared Equity Management L.P. is an investment adviser whose affiliates have sponsored two SPACs: G Squared Ascend I Inc. (GSQD 0.00%↑) and G Squared Ascend II Inc. (GSQB 0.00%↑). In dual IPOs last year, the blank-check companies raised $300,000,000 and $125,000,000, respectively, on the promise that their shared management team–which also manages G Squared Equity Management–would conduct a diligent search for attractive acquisition targets in the tech industry.

The team didn’t have to look far. In Sep. 2021, G Squared Ascend I announced a plan to merge with Transfix, Inc., which is a privately held logistics technology company whose existing shareholders just happen to include an affiliate of G Squared Equity Management. In other words, the investment adviser scoured the world and found no better merger target than one that lets it get liquid on one of its affiliate’s holdings. The proposed merger would value Transfix at $1,100,000,000.

The prospectus for G Squared Ascend I portrays the SPAC’s managers as seasoned venture capitalists who have funded high-profile tech startups such as Airbnb, Inc. (ABNB 0.00%↑), Lyft, Inc. (LYFT 0.00%↑), and Spotify Technology SA (SPOT 0.00%↑). But G Squared’s managers weren’t among the Silicon Valley elite who got to invest in those companies before anyone had heard of them.

Rather, G Squared acquired more than 70% of its investments on the secondary market. That is, the firm bought shares secondhand from early investors and employees who wanted to exercise their stock options and cash out–perhaps to put a down payment on a house or to send a kid to college. There’s nothing wrong with that. But if you think investing in a G Squared SPAC amounts to getting in early on the next Airbnb or Lyft, you may want to read further.

What’s in a name?

Several entities that bear the G Squared moniker used to have the acronym GSV in their names. Before that, many of them used to carry the brand name Gentry–as in Gentry Financial Holdings Group, LLC, which was founded in Chicago in 2008 by G Squared’s chairman, Larry Aschebrook. As the name implies, Gentry Financial Holdings Group was a holding company for several financial services businesses, including a securities brokerage named Gentry Securities, LLC. Aschebrook was a licensed broker with Gentry Securities until he ran into some trouble.

In 2013, an investor allegedly purchased an interest in a fund affiliated with Gentry Securities that failed to raise capital, according to records in FINRA’s BrokerCheck database. The investor claimed that Gentry owed him principal, fees, and warrants, and he demanded damages of $720,000. In a written response submitted to FINRA, Aschebrook said the complaint was inaccurate and that no assurances were made to the investor that the fund would raise all the money it required. The investor ultimately withdrew the complaint.

However, in the same year the complaint was lodged, an investor named Michael Bromiley sued Aschebrook, Gentry Capital Advisors, Gentry Financial Holdings, and an investment vehicle named Gentry-Solexel Investment, LLC, which Gentry Securities had sold to investors in a private offering. The vehicle held shares of Solexel, Inc. (a.k.a. Beamreach Solar, Inc.), which was a privately held solar tech startup in Milpitas, CA. The company allegedly raised $250,000,000 from investors before filing for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 2017. The lawsuit against Aschebrook and Gentry continued into 2015 before the parties settled on undisclosed terms.

In the same year the settlement was reached, another investor who had purchased interests in multiple investment vehicles affiliated with Gentry Securities alleged that the brokerage had made misrepresentations, had failed to disclose conflicts of interest, and had sold him unsuitable investments, according to BrokerCheck. He demanded damages of $236,713. Aschebrook and Gentry’s successor settled for $140,000. In a written response submitted to FINRA, Aschebrook said the complaint was inaccurate and that the investor had understood what he was getting into.

Reboot, Rebrand, Repeat

Before the complaints and the lawsuit were resolved, Aschebrook shut down Gentry Securities and moved on to a brokerage in Tampa, FL named Harbor Light Securities, LLC, according to BrokerCheck. He picked up where he had left off, using Harbor Light to sell private placements of funds managed by Gentry affiliates. Four months after he joined Harbor Light, Aschebrook’s holding company, Gentry Financial Group, announced that it was changing its name to GSV Financial Group and was giving its affiliates new names beginning with GSV. The company had licensed the GSV brand, which stands for Global Silicon Valley, by entering into an agreement with an investment adviser in Woodside, CA named GSV Asset Management, LLC, which became a sub-adviser to GSV Financial Group’s funds.

Not all was harmonious inside GSV Asset Management. In Dec. 2014, a co-founder of the investment adviser, Stephen Bard, sued his fellow managers. Among his beefs were allegations that the other executives had sought to dilute his ownership in the firm by surreptitiously forming and funding competing entities, including the renamed Gentry companies. Bard’s complaint alleged that his co-founder Michael Moe had grown resentful after Bard complained about Moe’s use of the firm’s funds to finance personal debts, an exorbitant lifestyle, and “lascivious non-business expenses.” Bard did not prevail in the lawsuit.

Through the rebranded GSV entities, Aschebrook intensified his practice of buying secondary shares of established tech startups, transferring the shares into funds, and selling interests in the funds via private placements. Regardless of how the funds performed, a GSV entity usually received a percentage of assets under management as a fee. Some of the funds–such as those that held shares of Airbnb, Lyft, and Spotify–generated handsome returns after the issuers went public. But other funds disappointed–particularly those that held shares of startups in which GSV entities had invested directly. Two such funds owned shares of Aquion Energy, Inc., which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2017 after GSV Ventures (née Gentry Venture Partners) had offered investors over $21,000,000 of interests in funds that held the company’s shares.

Birth of a SPAC

By the time Aquion Energy had restructured its debts and sold off assets, GSV Financial Group had already undergone another name change. The holding company’s flagship investment adviser, GSV Equity Management, LLC, was rechristened G Squared Equity Management L.P. and began raising new funds under the G Squared brand name. In 2019, a Cayman Islands affiliate of the adviser named G Squared Ascend Management I LLC acquired 761,607 shares of preferred stock at $10.49 per share in a Series D financing of Transfix, Inc.––which brings us back to the SPAC named G Squared Ascend I, Inc.

The SPAC went public on Feb. 8, 2021. As is customary with a blank-check company, the prospectus for G Squared Ascend I stated that the company had not identified a merger target as of the date of the IPO. But the prospectus also disclosed that G Squared Ascend I was not prohibited from pursuing a merger with a business that was affiliated with its sponsor, officers, or directors. On May 16, 2021, while said officers and directors were presumably hunting for a company to take public, a venture capital fund they managed named G Squared V, L.P. agreed to purchase up to $50,000,000 of convertible notes from Transfix. Under the terms of the purchase agreement, the notes are convertible into common stock of Transfix upon closing of a merger with a SPAC. Thus the managers of G Squared Ascend I had even more to gain from a combination with Transfix.

For the first nine months of 2021, Transfix reported unaudited revenue of $208,125,000, which represented a 73% increase from the first nine months of 2020. Although the top-line growth was impressive, the company’s thin gross profit margin of 5.7% barely budged from the same period in the prior year. For the nine months ended Sep. 30, 2021, Transfix reported unaudited operating and net losses of $26,446,000 and $28,173,000, respectively. The company is developing technology that aims to do for trucking what Uber and Lyft did for passenger transportation. But the cost that Transfix pays a carrier to move a load is its largest expense and one over which it has limited control.

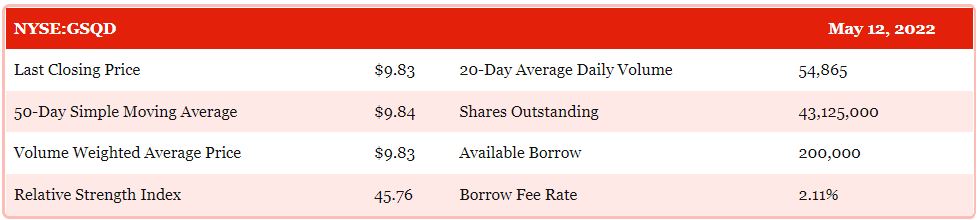

A year ago, investors were valuing companies like Transfix on a multiple of projected revenue. But how fast the market has changed. Suddenly, a $1,100,000,000 valuation for a company that barely squeaks out a gross profit looks like a stretch. Add to that the obvious conflicts of interest and mixed track record of the SPAC sponsor, and G Squared Ascend I may be a de-SPAC to short–if a de-SPAC occurs.